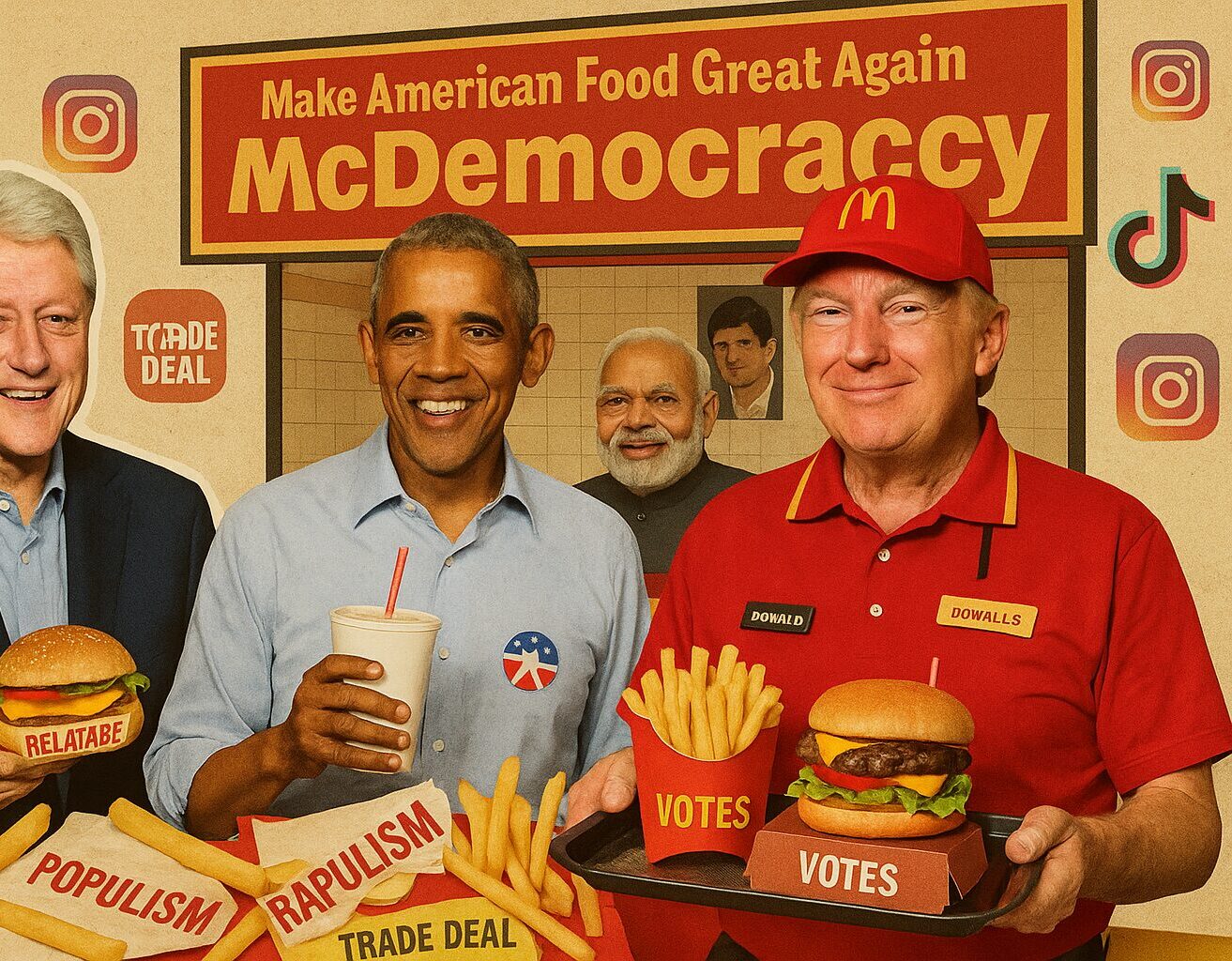

In a time when every bite can be a message and every meal a media moment, food has entered the political arena with surprising force. The 2024 U.S. presidential campaign saw Donald Trump donning a McDonald’s cap and manning the counter in Iowa, serving burgers and selfies in equal measure. It wasn’t just a publicity stunt—it was a strategic signal. Food, especially fast food, has become an unlikely yet potent political symbol: populist, accessible, and media-friendly. From Bill Clinton’s jog-stop at McDonald’s to Obama’s burger outings and global counterparts mimicking the formula, a clear message emerges: eating like the average citizen helps you seem like one.

In the United States, where food culture has long served as a mirror of social and economic trends, this performative consumption now plays into deeper national narratives. It cuts across voter demographics, fuels meme factories, and even ties into trade policies. More than ever, politicians are not just campaigning in diners—they’re campaigning through food.

Trend Snapshot / Factbox

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Trend name and brief definition | Political Fast Food: the strategic use of accessible food, especially fast food, as a tool of political messaging |

| Main ingredients or key components | Burgers, fries, soda, coffee, donuts, pizza |

| Current distribution (where can you find this trend now?) | U.S. presidential campaign trails, social media, press conferences, international populist campaigns |

| Well-known restaurants or products currently embodying this trend | McDonald’s, Burger King, Tim Hortons, local diners, street vendors |

| Relevant hashtags and social media presence | #TrumpMcDonalds, #ObamaBurger, #ModiEatsLocal, #CampaignMeal |

| Target demographics (who mainly consumes this trend?) | Working-class voters, middle-class families, undecided voters, social media users |

| “Wow factor” or special feature of the trend | Combines relatability, media virality, and economic symbolism |

| Trend phase (emerging, peak, declining) | Peak (particularly in U.S. election season) |

The Politician in the Drive-Thru Lane

Donald Trump has long capitalized on the cultural currency of fast food. His preference for McDonald’s, well-documented since his presidency, culminated in a 2024 campaign move that was equal parts media spectacle and populist strategy. By working a shift behind the counter at a McDonald’s in Iowa, Trump visually reinforced his alignment with everyday Americans, bypassing the traditional optics of political elitism.

This tactic isn’t new. Bill Clinton famously stopped for Big Macs during jogs in Little Rock, embodying a folksy charm that contrasted with his Ivy League background. Barack Obama, too, made a point of patronizing local burger joints and casual diners with his family. These moments, often amplified by news coverage and social media, convey more than personal taste: they signal relatability, accessibility, and normalcy.

International leaders have adopted similar strategies. Justin Trudeau’s carefully documented stops at Tim Hortons, Matteo Salvini’s Instagram posts from pizzerias, and Narendra Modi’s visits to street food vendors all follow the same playbook: eat where the people eat, and the people might just vote for you. The underlying logic is straightforward: fast food is inexpensive, omnipresent, and symbolic of mass experience. Eating it — and being seen eating it — sends a message of unity and humility.

Global Stage, Local Plate

Food is more than sustenance in political campaigns. It’s a medium of cultural and national identity. In America, fast food chains like McDonald’s or Dunkin’ have long stood as symbols of U.S. consumer culture. When politicians embrace these institutions, they reaffirm a nostalgic vision of American life that appeals across ideological lines.

Beyond the U.S., food plays a similarly symbolic role. Leaders like Recep Tayyip Erdoğan stage visits to working-class tea houses, evoking a sense of rootedness in tradition and community. Emmanuel Macron, often seen as the embodiment of French elitism, has made efforts to counter that image by visiting rural bistros and cafés during campaigns. The performative element is not lost on voters, nor on political consultants. It’s a language that transcends policy papers: eat the food of the people, and you become one of them.

Yet, critics point out the contradictions. While promoting proximity to the masses, these photo ops are often tightly choreographed. The same politician photographed with a burger might support legislation that cuts food stamps. The irony is rarely addressed in real time—but it underscores the risk inherent in performative populism.

Viral Meals and Memes

In the age of social media, every meal is a potential media event. A politician biting into a corn dog at a state fair can become a meme, a campaign ad, or both. Trump’s McDonald’s shift generated thousands of tweets, TikTok remixes, and Facebook shares within hours. These moments are easily digestible—both literally and digitally.

Obama’s love of Five Guys, captured in casual photos and shared online, contributed to his image as a modern, approachable leader. Even failed food moments—like awkward attempts to eat local delicacies—can humanize politicians. The risk is part of the reward. If the meal looks authentic, the message spreads faster than any press release.

This viral dynamic turns food into a soft power tool. It creates emotional touchpoints with audiences, especially younger voters, who are less engaged with traditional political content. Platforms like TikTok and Instagram thrive on this kind of visual storytelling. And in a landscape dominated by attention metrics, a hamburger can sometimes speak louder than a stump speech.

Eating America: Trade, Identity, and the Food Supply Chain

Beneath the symbolic value of political eating lies a realpolitik of food economics. The United States, despite being an agricultural powerhouse, imports more food than it exports in categories like fresh produce, wine, and seafood. Mexico supplies much of America’s vegetables and fruits; Canada exports significant amounts of meat; the EU, wine and specialty products.

Meanwhile, U.S. exports include bulk commodities like soy, corn, wheat, and increasingly processed foods and meats. These flows of goods have turned food into a policy flashpoint, especially in debates about trade, tariffs, and domestic agriculture.

Calls to “eat American” or “buy local” often surface during campaign cycles, but the reality of modern supply chains makes full food independence nearly impossible. Politicians invoking food patriotism may be gesturing to an ideal that global trade has rendered obsolete. Nonetheless, food remains a potent symbol for nationalist rhetoric and economic anxiety.

Calories and Constituents

Why does this work? Fast food, despite its unhealthy reputation, is comforting, familiar, and shared across social strata. It functions as a unifying cultural element in a fragmented society. When politicians eat it, they tap into a collective memory: childhood treats, late-night drive-thrus, road trips.

This familiarity creates emotional resonance. It reduces the psychological distance between voter and candidate. But it also risks trivializing deeper systemic issues—like food insecurity, labor exploitation in the food industry, and the health consequences of poor diet.

The optics of eating with the people are powerful, but they are not policy. As performative political food moments proliferate, so too does the need for scrutiny. Who benefits when a leader eats a burger on camera? And who pays the real cost when that same leader cuts subsidies or trade protections?

Burgers, Borders, Ballots

Food has always carried meaning. Today, in the high-stakes world of political performance, it has become a curated message. Whether it’s a Whopper on the campaign trail or a slice of pizza at a union hall, what politicians eat — and where they eat it — signals values, allegiances, and aspirations.

Yet while burgers may win hearts, they don’t necessarily feed change. As food continues to be used as a shortcut to empathy and identification, the challenge remains: moving from edible symbolism to substantive policy that nourishes more than just a narrative.